The Introduction to We Fell Into a Welfare State was published earlier and can be found here.

We all worked hard to create a better life for ourselves and our families. Generally speaking, in spite of lip service otherwise, the focus was on ME. We did what was necessary to advance in our career, move to other locations, work long hours, take opportunities. While some concern was expressed for others, the message remained Me First which by osmosis has been passed on to the next generation. – Joe Foster, Basic Income advocate

Summers used to be great. When the hottest it got was 26…when you could go outside and breathe without choking on smoke…when u could buy a home out west and not worry your city will be burned down in a wild fire…when you could go out and play and not get lymes disease or some other tic illness, when you could go to the beach or camp and swim in your lake without E.coli and blue algae making it deadly…..I think the boomers and their spawn have completely dropped the ball, have fucked over future generations and couldn’t care less….stick that in your lungs and choke on it….presently here in southern Quebec the smoke is so thick its making me sick….nice – An irritated Gen-X-er on Facebook

Gen Z doesn’t need a year of national service. They’re already drafted into decades of service for older Canadians. – Paul Kershaw[1], UBC Professor and Founder, Generation Squeeze.

Boomer-bashing has become Germany’s latest intellectual fashion. In his new book “Nach uns die Zukunft” (After Us, the Future), Marcel Fratzscher, president of the German Institute for Economic Research, delivers a sweeping indictment: hardly any generation since the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution has robbed its children and grandchildren of as many opportunities for a good and self-determined life as today’s baby boomers. Peter Bofinger[2], German Professor of Economics

I want to talk about boomers with a focus on Canada. I’m hoping you will help me with your thoughts and memories. We will explore what we did and what was happening at the time we did it. And we will do that in subsequent chapters. But first, an overview of our sins seems in order.

There is pretty compelling evidence against the baby boom and our social, economic, environmental and political record. But I wanted an objective view, so I asked ChatGPT what it thought and the answer was:

Taken together, the evidence suggests that while Baby Boomers benefited from postwar prosperity and catalyzed social progress, their demographic weight, policy choices, and cultural legacies have created structural burdens. These manifest as economic inequality, overstretched welfare systems, weakened family obligations, and a degraded environment — all disproportionately affecting Millennials, Gen Z, and future cohorts.

So here are eleven ways we changed the world:

1. It was all about us

We were idealistic and innocent at first. Then maybe not so innocent. And the idealism kind of morphed into something more diverse and fluid. Our numbers and our parents’ affluence gave us social power, which we exercised casually and arrogantly. The burgeoning middle class that evolved from the post war industrial boom and the unionization that accompanied it was, like our parents, the object of our derision. As Jacques Brel[3] put it, “The middle class are just like pigs, The older they get the dumber they get … We showed them our good manners … and we showed them our ass.”

Our numbers – 8 million of us versus about 4.7 million of our parents – came not only from more children, but more of us surviving into adulthood. Clean water, hygiene, vaccines and antibiotics to reduce infant death, prevent and survive childhood disease. More years in schools, safer tools, and no wars to thin us out in our youth.

Our needs – for schools, medical care, recreation, community colleges and universities – dominated family spending and political choices. Fortunately, the manufacturing, roadbuilding and housing boom that followed the war provided good jobs for our parents – usually for the men while women were homemakers. They migrated to the towns and cities for work, spreading the nuclear family. The tv show Father Knows Best epitomized the economy and the patriarchal social order of the day.

2: We rejected moral authority

Then we grew up and our tastes – for music, sexual freedom, entertainment and drugs – created behavioral patterns that persist to this day. Sports, music and film became mammoth industries. The bands, players and actors became the working rich, and many remained top performers for decades, with hero movies and tv series remade multiple times.

We insisted on freedom. And we rejected authority, at least over us. Like the church, the military and our parents. We declared God to be dead. We supported our American brethren in their opposition to war. We had a flirtation with liberation theology and the work of the Jesuits in Latin America in resisting military dictatorships and human rights abuses. We read Che Guevara, Paulo Friere, Ivan Illich, and other Marxists.

Although many of us grew up with racial and religious stereotypes deeply embedded by our culture and our socialization, we began to transform society with our support for civil rights. There was a strong focus on the US, where the battles were frequent and violent. However, there were spillover effects in Canada, in treatment of blacks, Chinese and Japanese, and eventually, and much delayed, Indigenous peoples.

But most of us got through the hippie phase …

3. We made education, not unions and worker solidarity, the key to security

Education was a ticket to a good-paying job. Whereas our parents’ generation entered the labour force early, after 8 -10 years of schooling, the baby boom tended to complete high school or university, with 12 or more years of schooling. And there were twice as many of us. But the more education, the better the job.

Postsecondary enrollment doubled between 1960 and 1970 and doubled again by 1980. We expanded the occupational playing field, especially in social sciences, health sciences and humanities. Teachers and nurses were in demand, attracting especially women. There was more public sector, corporation and institutional employment. Credentialism began to emerge as more jobs required formal education credentials. In time this would come to divide the labour force.

4. We brought in feminism and changed work and family

Our big domestic social revolution was feminism. Its roots were earlier in the suffragette movement, as well as civil rights activism. As the rights to vote, hold public office and enter legal contracts were achieved, the focus turned to higher-level occupations, fair recruitment, and equal pay.

Women gradually achieved equality or something close, in the workforce. Their movement was so strong that, although issues still exist (some – not all – of which are legacy effects or lifestyle choices) women have now surpassed men in many professional education programs and in the professions themselves. And most of the patriarchal attitudes were overcome, with women no longer seen as a weaker species needing male protection. (I remember getting a verbal jab for opening a door for a female co-worker. But that was a sign of the times.)

But feminism has been criticized from within (by bell hooks[4], an African-American feminist, and others) for concentrating their efforts in the professional categories, while being less concerned with racial minorities or lower-income women. In the 80’s, when their power and impact were pushing political, economic and social boundaries, the movement expressed little concern that the expanded labour supply was permitting employers to downgrade working conditions for the bottom half of the workforce.

Our editor David Newman points out that not all of our sexual freedom was exercised in support of feminism. Playboy, Hustler and Penthouse magazines and the adult porn film industry, all grew and flourished, as did hedonism and chauvinism. A lot of male support for the “burn the bra” movement was motivated not by support for feminism but by the view of women without bras. We also cheered when the cheerleaders did cartwheels.

Families

From the late sixties to the late eighties, we shifted from having two-thirds of families being one-earner, to more than two-thirds of a fast-growing number of families having two earners. Our impact on the labour market was huge. In 1966 there were a bit over 7 million people in the labour force, and by 1986, the number had increased to over 12 million.[5] No wonder our economy grew.

What we didn’t do was have as many kids. The number of children per woman decreased from 3.9 to less than 2. Our smaller families with two earners jolted upward the economic power of the family unit. We bought houses and cottages and big cars. Two of them. An up-market population grew, coinciding with “assortative mating” – doctors and lawyers and other professionals married each other, not their secretaries or nurses. Or they started out with them and then moved on. As families became smaller, we contracted out much of the child raising – nannies, childcare, summer camps; tennis, ski, watersports, hockey leagues. The “Y” provided some levelling of the playing field, but a class difference was creeping in.

Divorces bloom

When a federal unified divorce act was put in place to replace provincial legislation in 1968, it provided for marital breakdown, as well as adultery or abuse, as reasons for divorce. It was amended again in 1985 to include no-fault divorce after one year of separation. There were 11,343 divorces in Canada in 1968, 29,700 in 1971, and 96,200 in 1987. We were finding it hard to adjust to the new sexual freedom and prosperity, and our families paid a price.[6] As one consequence, low-income female-led lone parent families became commonplace. By 1995, 22% of all families with children were lone-parent families,[7] over 90% female-led. I wrote a book about it at the time[8]. Other children got used to being shuffled between the parents and integrating into blended families.

5. We lost sight of what was happening to the work force

Despite growth in high-paying jobs, all workers were losing bargaining power. In part it was because there were so many people looking for jobs, but the effects were largely hidden by dual-earner families. In parallel, companies were finding ways to undermine worker power, and big business was gaining control over government economic policy.

In 2008 Sharpe, Arsenault and Harrison attempted to explain why the median earnings of full-time, full-year workers in Canada rose only $53 between 1980 and 2005. Over the same period, total economy labour productivity gains were 37.4 per cent.[9]

The reason was that the returns to increased productivity were going to capital, not to labour. But again, it was masked by the increased earnings of two-earner families.

Unions were sidelined by franchising of retail outlets to independent operators, which made it impossible to bargain with one employer. Companies were also finding that it was cheaper to produce their goods in Asia and ship them back to North America than to pay Canadian or American wages.

In face of these threats, boomers took part in the evolution of two-tier workplaces, where current employees tried to secure their futures by bargaining away essential protections for the younger generation. They allowed employers to bring in casual workers, temps, part-timers, and contract workers who did not become part of the union. This also happened in public service unions who were not faced with extinction but simply took better arrangements for themselves at the expense of following generations. In addition, the development of a “shadow” work force[10] of experts, content specialists and consultants, has provided public service managers with a means to avoid the cumbersome recruitment methods. Unfortunately, It also means that over time, the expertise that used to exist in public service bureaucracies has been gradually stripped away.

6. We welcomed Neoliberalism

As neoliberalism – supporting limited government and unregulated capitalism – began to take hold in the late seventies and the eighties, the baby boom did not resist very much. The free trade proposition was presented to Canada by the MacDonald Royal Commission. Canadians voted for free trade and cheaper consumer goods, knowing that manufacturing workers would be displaced and private sector unions undermined. The wages and working conditions of insecure workers would deteriorate. But the economy would grow, providing professionals with better opportunities and lower priced, bigger televisions. Private sector unions covered about 32% of workers in 1970 and about 17% in 2010.[11] The decline of organized labour as a progressive force is a decisive factor in Canadian history, and cannot be quickly sumarized. We will take it up later.

With globalization, the business community took control of trade, economic and foreign policy of governments. They wanted free movement of money and free, unregulated trade, and they promised greater prosperity. International agencies like the World Trade Organization were co-opted into supporting global economic expansion at the expense of political guardrails. Companies gained the capacity to sue governments that made regulatory changes that impinged on their business. These restrictions have become a significant obstacle to the introduction of environmental restrictions on economic activity.

Individual and corporate wealth brings not only economic power, but also political power. So far Canada seems to have been spared from the obscenity of oligarchs devouring public resources for their own private uses, as we see in the US and elsewhere. But we might not be so far away. Our industry is becoming ever more concentrated and forceful in pursuing its objectives through government, especially the oil industry. And because much of our industry is foreign-owned and foreign-controlled, we are economically vulnerable. Interesting, as Canada is being threatened with a devastating tariff wall by Donald Trump, that a generation which watched the development of precarity on the edges of the labour market, is now seeing that their whole economy has become precarious.

7. We consumed our way into an environmental crisis

Most everyone will tell us that we have screwed up the earth’s capacity to sustain humanity and other vulnerable species. It wasn’t that we were not warned:

The 1972 Limits to Growth report by the Club of Rome clearly presented the implications of our patterns of producing and consuming and warned that exponentially increasing economic growth would eventually exceed “planetary boundaries”. Instead of reducing our consumption, we increased it – not only collectively as might be assumed because we were large numbers, but also our consumption per household increased.

The UN Conference on the Human Environment 1972 warned of the dangers of pollution, biodiversity loss and sustainability. It led to the UN Environment Program, which has struggled ever since to convince us to change our consumption patterns.

A report entitled “Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment” (1979), by the US National Academy of Sciences, reported on the scientific consensus on the role of CO2 in global warming.

The U.S. National Academy of Sciences Report (1975) – Marine Pollutionquantified marine debris, including plastic dumping.

In the 1980s, Greenpeace and other environmental organizations mounted campaigns targeting plastic pollution, toxic waste and the role of large corporations in maintaining the behavior that would threaten humankind. They made some headlines but did not effect significant change.

The Bruntland Commission report of 1987 introduced the concept of sustainability and provided a roadmap to a sustainable planet, in preparation for the 1992 Earth Summit.

Charlie Angus tells us[12] that the big oil companies carried out substantial research in the late 70’s and the 80’s, – research that accurately predicted the effects of fossil fuel production and consumption on the environment and temperature of the planet. According to Charlie, they decided to hide the research and continue making big profits. Fossil fuel markets expanded, automobile and air travel expanded, and we went heavily into plastics and landfills. When our own landfills were saturated, we started shipping our garbage to poor countries. We increased consumption in housing and household goods, the heating and cooling of ever larger homes, the dependence on the automobile, the mass production of food.

There were many other reports that warned us clearly of the environmental impact of our behavior. We spawned environmental groups, but their efforts were not strong enough. They did not receive enough support from the people whose votes counted in national elections – the boomers. We could not mount the social consensus required to overcome our desire to acquire.

8. We let government lose sight of people

Boomers supported and benefitted from the dramatic expansion of government, at all levels, beginning in the 1960’s. They worked for them and voted for expanded benefits. Unfortunately, they also supported reductions to the top marginal tax rates, shielding themselves. Instead, they supported flatter tax structures and sales taxes, which fall more heavily on people with low to moderate incomes.

Steven Pinker[13] says that since the 1960’s, despite major increases in the role and size of government, public trust in government and institutions has declined, to the point that in the 2000’s, populist groups which explicitly reject those institutions have been growing rapidly. This is a clear repudiation of boomer-built institutions. New political networks with intent to dismantle governments and civic institutions are gaining voter support. We can see the culmination of that distrust in Donald Trump’s assault in the US. The government agencies, courts, universities and news media are not only being attacked; they aren’t even defending themselves. In Canada, Pierre Pollievre promised to defund the CBC, trying to catch a whiff of Trump’s wind.

As a Guardian review of Thomas Chatterton’s book, Summer of our Discontent puts it, his book … tells us that the self-preening, race-mad identity politics of left-leaning liberals has fostered atomization and precluded solidarity. As a consequence, the illiberal, unhinged right, now united behind Trump, has stolen a march on them.[14]

Pinker’s observation follows on many others. Robert Putnam, in his essay Bowling Alone[15] in 1995, documented the decline in membership of civil society organizations, including churches, in America. He equated civil society with social capital, which he considered essential to complement and sustain democratic government. Active engagement in the affairs of the community is an essential dimension of social capital. Declining civic participation, mirrored by declines in voting percentages and newspaper reading, suggested a loss of social trust. A fall-off of church membership and attendance paralleled these processes in both the US and Canada. In yet another paradox, much of today’s extremism and authoritarianism is clearly and ostensibly attributed to fundamentalist religious doctrines and propaganda.

9. We split the middle class

In Canada, Posner and Gregg[16] in 1990 pointed to a split in society, saying that in the mid-eighties, an evident change became visible in the polls. Where before everyone believed they were middle class or could become that, now they were dividing into haves and have-nots. It was during the eighties that high levels of unemployment permitted employers to require higher levels of education as entry criteria to almost any job, while governments froze minimum wages. The beginning of a bifurcation in the labour market that would be deepened by the hollowing out of manufacturing as a provider of middle-income blue-collar jobs.

What had been a boomer aspiration to level economic classes and even see social class as an anachronism led to public promotion of the professional class and those aspiring to join it, along with the dominance of the 1% and the those aspiring to join it – the new oligarchy.

Inequality

We are told by Thomas Piketty[17] and others that economic inequality was on the decrease until the baby boom entered the labour force, and then the trend reversed. In a series of federal budgets in the 1970’s and 1980’s top marginal income tax rates were drastically reduced in favour of consumption taxes, which hit the middle and lower income ranges hardest.

Economic inequality measured by income and by wealth, has moved beyond all proportion. Statistics Canada reported recently that income inequality has reached a record level in 2025[18].

10. We lost sight of people who need help, and left them by the wayside

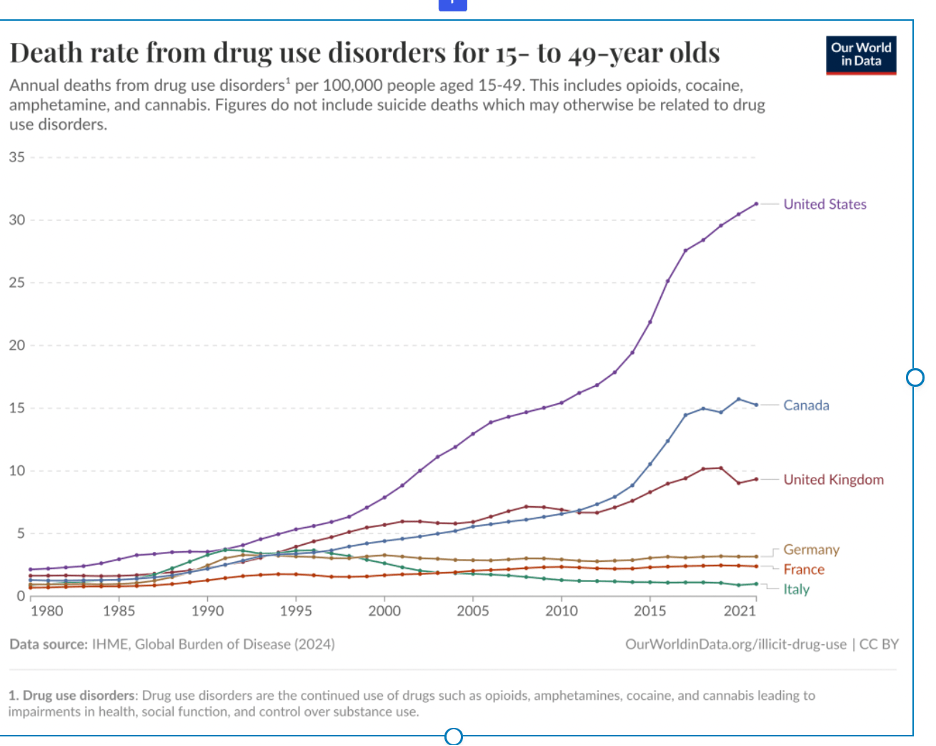

Drug use and deaths

We brought drugs into the mainstream, first experimenting, then adopting them in regular use. We refined them and made them more effective and stronger. Now some of them are now legal, which is good. And some are lethal. It was not our initiative, but we allowed harmful drugs to flood our market.

As the following screenshot shows, Canada has an unenviable record with drugs.

In the 80’s, we closed institutions for the disabled and sent them into the community. Some benefitted and did well. Many didn’t and wound up living on our streets. A well-meaning but misguided charitable sector built emergency shelters, soup kitchens, food banks, to give people sustenance – but not to provide money or secure housing. We built an infrastructure and created conditions for bad drugs, violence and misery. And it is still growing today. We had crack cocaine in the 80’s, crystal meth in the 90’s, and fentanyl and carfentanyl more recently. Our homeless population and drug-addicted population are intertwined, and we have no proven way of dealing with the problem. Once-vibrant, upscale urban communities have been converted into dangerous slums inhabited by young professionals who are socially isolated, afraid to come out of their high-rise condos.

11. Now we are draining away the incomes of our children

Many young people feel that they will not be as affluent as their parents. Several support an organization called “Generation Squeeze[19]” whose spokesperson economist Paul Kershaw repeatedly points out that the OAS is the largest expenditure in the federal budget and is equal to the federal deficit. He argues that boomers are the wealthiest generation and should be more highly taxed, or have age-related benefits reduced. He claims that boomers required five years of work to save a 20% down payment for a house, whereas Gen Z needs 14. And he asks why a boomer household can have $182,000 income (split equally) and not have their OAS reduced, whereas a younger household with kids will have their child tax credit reduced at around $81,000. But boomers still vote in large numbers.

Wealth

The inequality among income earners is less than the inequality in the distribution of wealth. We don’t have Canadian figures to compare for the early period, but the US boomers in 1989 held about 21% of national household net worth[20] – probably about equal to their share of the population at the time. By 2019, their cohort held about 54% of national household net worth, while Canadian boomers held 49.7% [21].

And we are a huge drain on the public system. We draw resources from the health care system, as we live much longer, even with multiple chronic and acute diseases. More of us live to old age and live many years in retirement, drawing from the OAS/GIS and CPP. About 70% of our parents lived to be 65, and then they lived an average of 16 years. About 88% of boomers reach 65 and then they live for about 20 more years. To put those numbers into perspective, a little (overly-simplified) arithmetic. 70% of 4.7 million of our parents equals about 3.3 million, living an average of 16 years – so a bit over 50 million person-years of medical and pension supports. That is the system we built for our parents. But we – 88% of us or over 7 million, live 20 years – so about 140 million person-years of medical and pension support – that we are asking our children, who number about the same as us, to support. Paul Kershaw has a point. And although the baby boom is about to pass on huge wealth to their children, we are told that the intergenerational transfer will entrench existing inequalities.

In all, it seems to be a serious reproof of a generation which in its youth promised to fix the world. A study by economics student Shelly Kaushik indicates that boomers voted more left than their parents when they were young, and more right when they got older, a pretty good indication that they were intensely looking after their own interests[22].

But are we happy?

The World Happiness Report points toward a phenomenon in North America which differs from most European countries. Our younger generation is showing sharp reductions in their reported quality of life, while the older one is sublimely happy. The 2024 report places Canada at number 8 on the list of countries when people over 60 are asked how happy they are. But when those under 30 are asked, Canada falls to number 58 on the list![23] While most of the wealthy countries show some variance between the old and other age groups, the difference is far less. Canada and the US (#10 for the old, #62 for the young) show a huge gap. Clearly, something is wrong in North America.

But we are for the most part, complacent and secure in our old age. We like to travel the world, and often. The boomers in Canada are, in general, a happy lot.

Well, I’ve been pretty hard on my generation here. If I’m mistaken, I would like to know. In following chapters I will look more closely at the choices we made, why we made them, and what happened. Maybe find some good things that we’ve done. I invite your comments and suggestions. Did we know what we were doing? Were there mitigating outcomes? Good achievements? Does it balance out? You can comment by scrolling down. I have already heard from a few of you and will be using your contributions in later chapters.

Next Chapter: Growing up as a Boomer (coming soon)

[1] from LinkedIn, Sept 2, 2025

[2] Peter Bofinger, Germany’s Misguided War on Baby Boomers, Social Europe, 11 Sept. 2025

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Brel_is_Alive_and_Well_and_Living_in_Paris

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks

[5] Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey(s)

[6] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-503-x/2005001/tab/tab2-5-eng.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[7] Daily, June 19, 1996 – Lone-parent families

[8] Lone Parent Incomes and Social Policy Outcomes: Canada in International Perspective, Queens University, 1997

[9] https://www.csls.ca/events/cea2009/sharpe-etal.pdf

[10] https://www.policyalternatives.ca/wp-content/uploads/attachments/Shadow_Public_Service.pdf

[11] https://centreforfuturework.ca/2023/10/19/union-coverage-and-inequality-in-canada

[12] “Dangerous Memories” podcast.

[13] Pinker, Steven, Enlightenment,…..p52

[14] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/jul/22/summer-of-our-discontent-by-thomas-chatterton-williams-reivew-a-muddled-take-on-us-race-politics-and-class

[15] Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy, vol. 6 no. 1, 1995, p. 65-78. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002.

[16] Gregg, A, and Posner, M, The Big Picture; What Canadians Think about Almost Everything, MacFarlane Walter and Ross, Toronto 1990, p 14, 15

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Piketty

[18] https://thetyee.ca/News/2025/08/25/How-Rich-Canadians-Got-Even-Richer/?utm_source=daily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=250825

[19] https://www.gensqueeze.ca/expanding_medical_care

[20] https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/n675k6/share_of_us_wealth_by_generation_oc/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[21] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200626/cg-a001-eng.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[22] Voting Behaviour by Age and Generation: A Study of Canadian Elections from 1965 to 2015 By Shelly Kaushik An essay submitted to the Department of Economics in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts under the supervision of Professor Christopher Cotton

[23] https://www.worldhappiness.report/ed/2024/happiness-of-the-younger-the-older-and-those-in-between/

This is fabulous. Sid Frankel and I at BICN are working with Paul and Andrea at GenSqueeze which brings me to another general point linked to the others.

Given what’s happened with the workforce and what’s eroded in public policy, and what’s going backwards on gender and racial justice, insecurity has become a driving force. With almost no societal support for 18-64 year olds (jobs that provide little $ and no security, EI that people can’t claim, SA that’s cruelly low and punitive, AI disruption) anyone who can find a way to provide some economic security will take it, not out of greed necessarily but fear and self-preservation. Our income security system is tragically broken.

On gender equality, the environment and the neoliberal agenda, one of the big ironic things that went wrong was that at the same time as the boom generation came along and the UN was developing universal human rights, another part of the UN created a System of National Accounts based on GDP that establishes that non-market work and the environment are irrelevant to the economy but also free to abuse and exploit, with disastrous consequences for people and planet.

Guy Standing’s latest book, the Politics of Time, shows how many ways our time is being wasted and exploited, and that we are expecting people to do more work in its widest sense in order to be able to labour for pay (flight attendants expected to do unpaid work on the ground) while also competing now with robots. It’s another form of generational inequality that seniors (like me) get to have much more control of their time compared to younger people when they have income security and wealth. That could be a good thing if seniors’ time could be organized to support more progressive policy for their children and grandchildren.

Last point, based on a conversation between a Polish immigrant and a Chinese immigrant both complaining about recent immigrants (‘they don’t work’ – no recognition of how much has changed since this man arrived – and ‘Canada is stupid to let in immigrants who don’t share our values and don’t want to assimilate’ – their ‘values’ are capitalist, homophobic and Islamophobic). So we are going backwards on diversity too, not valuing its contribution to Canadian culture, economy etc. but as another reason to be divisive.

Some of us have been trying to resist the negative trends all along so we need to show those stories at some point too.

Just felt the need to share! Thanks, Sheila

>

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this, Sheila. You bring together many threads here, and I will want to come back to them in subsequent chapters. I think it is important to recognize that precarity is moving up the food chain, much as Guy Standing pointed out in his earlier book. Even where lower and moderate incomes have kept pace with inflation (and that is a questionable tenet, given that the low-income consumption basket does not correspond to what is usually measured) they have not kept pace with society. And the shifting vision of what is measured as economic activity – where a financial transaction takes place – distorts what we perceive as important. Lots to explore here, and I hope you will continue to contribute to this project. I think it is important that we find a perspective which can encompass complexity, while not becoming paralyzed by the same.

LikeLike